[Quant Math] Week 1: The Epsilon-Delta Definition of Limits

In Financial Engineering, particularly when modeling derivatives using Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) or the Black-Scholes framework, reliance on geometric intuition is insufficient. The concept of “continuous time” and “convergence” requires a rigorous mathematical foundation.

Before we can discuss volatility, Brownian motion, or Itô calculus, we must first establish the precise definition of a limit. This post covers the $\epsilon-\delta$ (Epsilon-Delta) definition, moving beyond the intuitive notion of “approaching” to a static, logical formulation.

We will examine three specific cases:

- A Linear Function (Basic application)

- A Quadratic Function (Handling variable rates of change via boundedness)

- A Step Function (Proving discontinuity via negation)

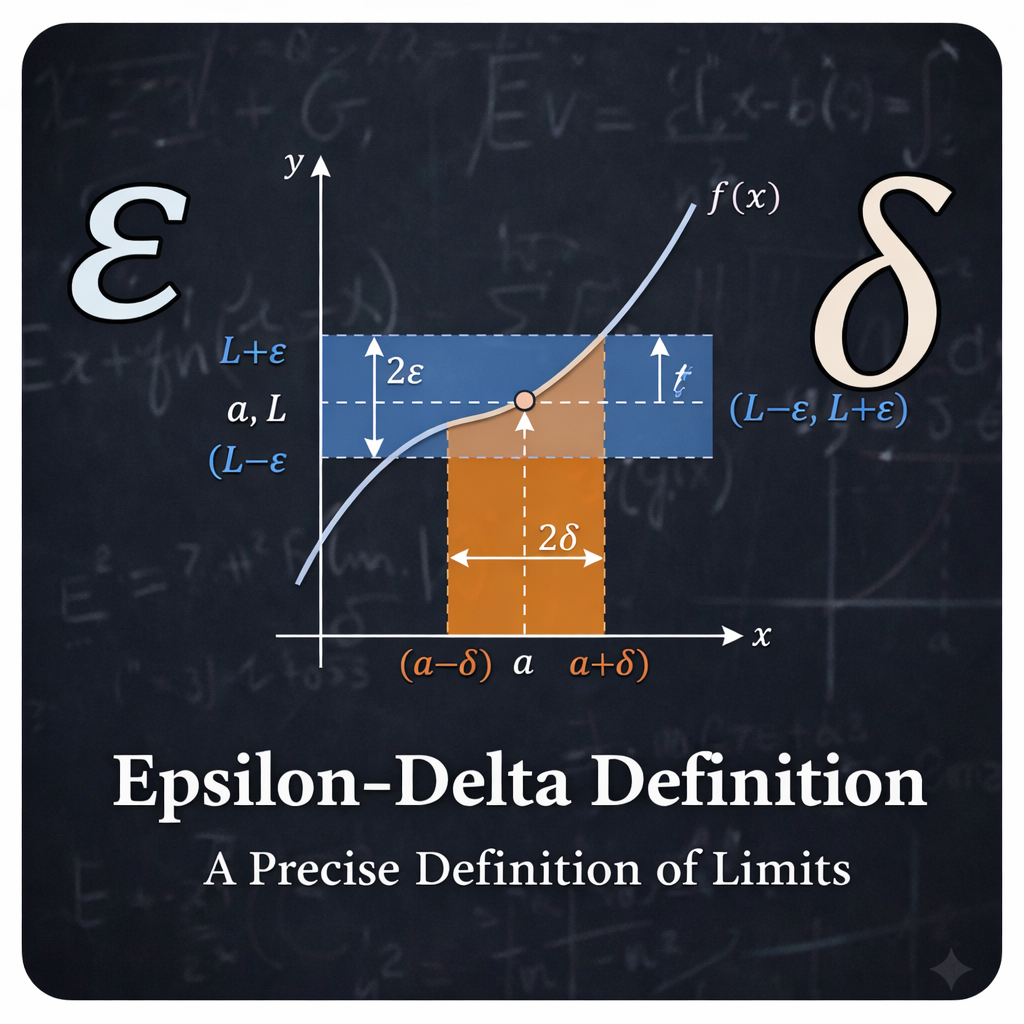

1. The Formal Definition

The statement $\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = L$ is defined as follows:

Definition:

Let $f$ be a function defined on an open interval containing $a$, except possibly at $a$. We say the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches $a$ is $L$ if:$$ \forall \epsilon > 0, \exists \delta > 0 \text{ s.t. } 0 < |x - a| < \delta \implies |f(x) - L| < \epsilon $$

Interpretation: For any arbitrary positive number $\epsilon$ (no matter how small), there exists a positive number $\delta$ such that if $x$ is within distance $\delta$ from $a$ (but not equal to $a$), then $f(x)$ is strictly within distance $\epsilon$ from $L$.

The core of the proof lies in determining the functional relationship $\delta(\epsilon)$. We must demonstrate the existence of such a $\delta$ for every possible $\epsilon$.

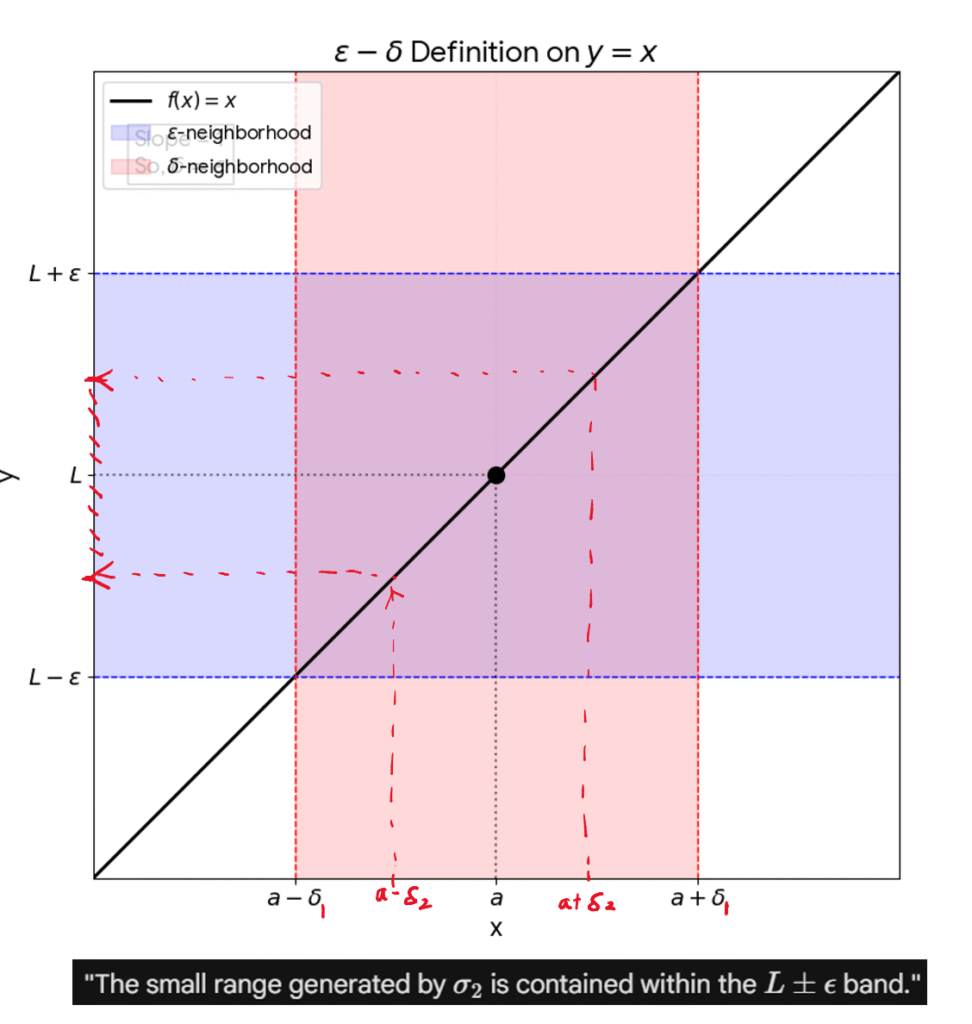

2. Case Study 1: Linear Function

Problem: Prove that $\lim_{x \to 2} (2x + 1) = 5$.

Phase 1: Scratch Work (Finding $\delta$)

We require the error $|f(x) – L|$ to be less than $\epsilon$:

$$|(2x + 1) – 5| < \epsilon$$

$$|2x – 4| < \epsilon$$

$$2|x – 2| < \epsilon \implies |x - 2| < \frac{\epsilon}{2}$$

This suggests that choosing $\delta = \frac{\epsilon}{2}$ will satisfy the condition.

Phase 2: Formal Proof

Proof:

- Let $\epsilon > 0$ be given.

- Choose $\delta = \frac{\epsilon}{2}$. Since $\epsilon > 0$, it follows that $\delta > 0$.

- Assume $0 < |x - 2| < \delta$.

- Then, substituting the function and limit: $$|(2x + 1) – 5| = |2x – 4| = 2|x – 2|$$

- Substituting the inequality from step 3 ($|x – 2| < \delta$): $$2|x - 2| < 2\delta = 2\left(\frac{\epsilon}{2}\right) = \epsilon$$

- Thus, $|(2x + 1) – 5| < \epsilon$.

- By definition, $\lim_{x \to 2} (2x + 1) = 5$.

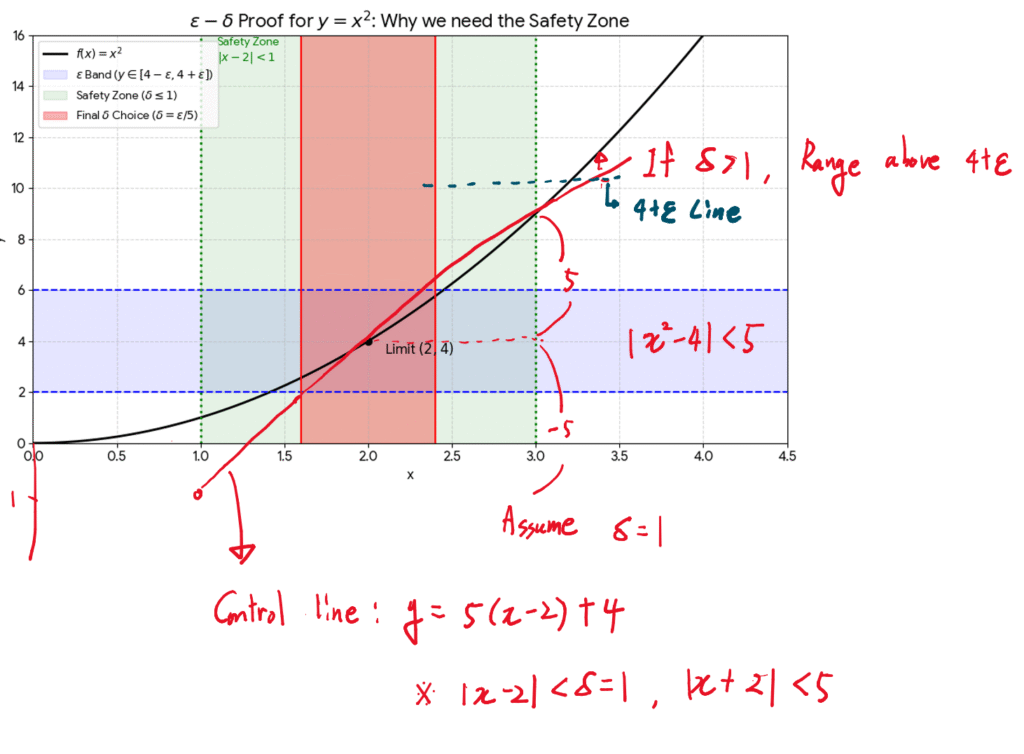

3. Case Study 2: Quadratic Function (The “Min” Technique)

Problem: Prove that $\lim_{x \to 2} x^2 = 4$.

Phase 1: Scratch Work

We analyze the error term:

$$|x^2 – 4| = |x – 2||x + 2| < \epsilon$$

We must establish an upper bound for $|x + 2|$ by restricting $\delta$ to a preliminary range.

- Preliminary Bound: Assume $\delta \le 1$.

Then, $|x – 2| < 1 \implies 1 < x < 3$. - Bounding the Uncontrollable Term:

If $1 < x < 3$, then:

$$3 < x + 2 < 5 \implies |x + 2| < 5$$ - Refining $\delta$:

Now the inequality becomes $|x – 2| \cdot 5 < \epsilon$, which implies $|x - 2| < \frac{\epsilon}{5}$.

Thus, $\delta$ must satisfy two conditions: $\delta \le 1$ AND $\delta \le \frac{\epsilon}{5}$.

Phase 2: Formal Proof

Proof:

- Let $\epsilon > 0$ be given.

- Choose $\delta = \min\left(1, \frac{\epsilon}{5}\right)$.

- Assume $0 < |x - 2| < \delta$.

- Since $\delta \le 1$, we have $|x – 2| < 1$, which implies $1 < x < 3$. Consequently, $|x + 2| < 5$.

- Consider the absolute difference: $$|x^2 – 4| = |x – 2||x + 2|$$

- Using the bound from step 4 ($|x+2| < 5$) and the assumption from step 3 ($|x-2| < \delta$): $$|x - 2||x + 2| < \delta \cdot 5$$

- Since $\delta \le \frac{\epsilon}{5}$, it follows that: $$\delta \cdot 5 \le \left(\frac{\epsilon}{5}\right) \cdot 5 = \epsilon$$

- Therefore, $|x^2 – 4| < \epsilon$.

4. Case Study 3: Discontinuous Function (Proof by Negation)

Problem: Prove that the following function $f(x)$ is not continuous at $x=0$.

$$f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } x \ge 0 \\ 0 & \text{if } x < 0 \end{cases}$$

Proof (Disproof of Continuity)

To prove the limit does not exist, we must show that for some $\epsilon$, no $\delta$ works.

Proof:

- Hypothesis: Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x) = 1$.

- Choose $\epsilon$: Let $\epsilon = 0.5$.

- Arbitrary $\delta$: Consider any $\delta > 0$. The $\delta$-neighborhood is $(-\delta, \delta)$.

- Find a Counter-example: Within the interval $(-\delta, \delta)$, there exists a number $x = -\frac{\delta}{2}$.

Since $x < 0$, by definition $f(x) = 0$. - Check the Inequality: $$|f(x) – L| = |0 – 1| = 1$$

- Contradiction: We require $|f(x) – 1| < \epsilon = 0.5$, but we found that $|f(x) - 1| = 1$, which is not less than 0.5.

- Conclusion: Since we found an $\epsilon$ for which no $\delta$ works, $\lim_{x \to 0} f(x) \neq 1$. Thus, $f(x)$ is discontinuous at $x=0$.

5. Why This Matters for Quants

In financial mathematics, the distinction between continuous paths (modeled by Brownian motion) and discontinuous paths (modeled by Jump processes, e.g., Poisson processes) is fundamental.

The rigorous $\epsilon-\delta$ framework allows us to formally define Continuity and Differentiability. These are the necessary prerequisites for understanding the Itô Integral, which is the engine behind the Black-Scholes equation.

Next Week: We will extend this definition to formalize Continuity and Differentiability, bridging the gap between calculus and stochastic analysis.